In the early 1970s, Nestlé faced a cultural impasse in Japan that no marketing budget could easily dissolve. Coffee, though globally ascendant, remained deeply incompatible with Japanese taste, tradition, and sentiment. It was bitter, adult, foreign, and - most damning of all - emotionally irrelevant. Conventional advertising had failed to seed any meaningful foothold, and product placement, celebrity endorsement, and packaging redesign had all produced negligible shifts in perception. The drink simply didn’t belong. It didn’t evoke nostalgia, didn’t sit comfortably in memory, and had no place in the domestic rituals of a post-war generation already steeped in green tea and ceremonial quiet. So Nestlé stopped trying to sell coffee to adults and turned, instead, to a far more enduring strategy: they decided to sell it to children.

They did not sell the drink, of course, not directly. They sold the experience. And in doing so, they rewrote the emotional associations that would come to define coffee not as a stimulant, but as comfort, not as a beverage, but as a ritual of belonging. This wasn’t marketing - it was cultural reprogramming. It was led by a man named Clotaire Rapaille, a French psychoanalyst turned brand strategist who believed that purchasing decisions were not driven by rational evaluation but by emotional imprints forged in early childhood. If you could plant a sensory association before language, before logic, before resistance, you could create not just loyalty but longing. You could bypass cognition entirely and forge a future consumer through memory alone.

Nestlé followed his advice with unnerving precision. They released sweetened, coffee-flavoured candies aimed at school-aged children, wrapped in foil that looked harmless to parents but carried within it the early trace of what would later become compulsion. They created toys and dolls that smelled faintly of roasted beans, not strong enough to be noticed, but sufficient to settle quietly into the ambient emotional backdrop of childhood. They embedded coffee not in messaging but in the margins: the aroma of warmth during story time, the treat that arrived after homework, the invisible thread linking love, safety, and flavour. By the time that child became an adult, coffee no longer had to be sold. The body already wanted it. The memory had already done the work.

It would be comforting to believe that such strategies remained confined to the past, to the analog world of candies and commercials. But the truth is far more confronting. The psychological engineering that helped Nestlé convert a nation of tea drinkers into lifelong coffee consumers has not vanished; it has been scaled, digitised, and redeployed at a velocity and reach previously unimaginable. And this time, the product is not coffee. It is content. And the raw material is not cocoa or caffeine. It is your child.

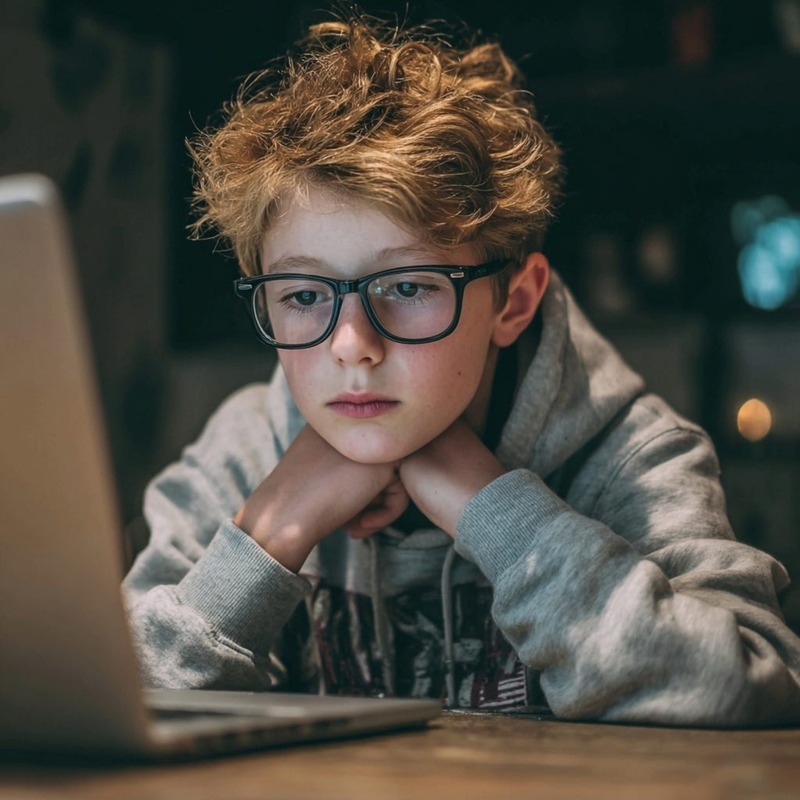

The modern equivalent of Rapaille’s coffee candy campaign is not a sensory object. It is a smartphone screen. It is an algorithmic feed optimised not for taste but for exposure, not for aroma but for behavioural traceability. Big Tech does not need to design a wrapper. It has designed a culture. It does not need to insert scent into toys when it can insert ideology into parenting. It does not need to convince anyone of anything, because it has already built the environment in which participation is framed as pride and privacy is framed as neglect.

What Nestlé discovered in Japanese children, Big Tech discovered in parents. That the fastest way to condition a human being is to start before they know what they are being conditioned for. And so the platforms stopped trying to sell attention and began instead to harvest memory. They positioned the performance of parenting as a public act, tethered to metrics and social approval, cloaked in intimacy but monetised through surveillance. They taught mothers to film tantrums and fathers to narrate hospital visits, not out of carelessness or vanity, but out of an engineered belief that documentation was synonymous with devotion. They taught us that a child’s life should be witnessed, not quietly but algorithmically, not within the family but across the feed.

As I detailed in my paper The Parental Influencer Industrial Complex, this phenomenon is not a glitch or a side-effect, but a fully-fledged industrial system that reconfigures parenting as production and children as content creators whose consent is neither requested nor required. It functions not through coercion but through calibration. The more intimate the post, the higher the engagement. The more vulnerable the moment, the greater the reach. The metrics do not reward care, they reward disclosure. And the algorithm does not care if your child is in pain, only whether the lighting is good and the caption “relatable.”

Parents, manipulated by the aesthetics of connection and the architecture of affirmation, find themselves incentivised to post more, expose more, share more - until what began as memory becomes media, and what began as love becomes labour. Their children, meanwhile, become digitally inscribed long before they can speak for themselves, their developmental timelines converted into data streams that feed predictive algorithms for insurance, education, behavioural analysis, and consumer profiling.

This is not science fiction. This is logistics. And just as Nestlé never needed a child to crave coffee in the moment - only to associate its smell with love - Big Tech does not need a child to understand the feed. It only needs the feed to understand the child.

There is no reset button. Once the association is forged, once the content is posted, once the data is absorbed, the system has already done its job. By the time the child becomes old enough to question their own digital footprint, that footprint has been monetised a thousand times over. The scent of coffee may fade. The imprint of exposure does not.

And so we find ourselves at the edge of a moral reckoning that most policymakers, platforms, and even parents have yet to acknowledge: that what we are participating in is not digital nostalgia but digital enclosure. That what we are uploading is not memory but labour. That what we are normalising is not love but surveillance wrapped in sentimentality.

Nestlé embedded coffee in the consciousness of a nation through the sensory manipulation of children. It was brilliant, and it was exploitative. Big Tech has embedded surveillance into the fabric of parenting itself. It is far more brilliant, and far more dangerous. Because it does not taste bitter. It tastes like love.

And that is how it gets in.